Research

Our work revolves around two central questions:

1. How do the neural mechanisms of memory break down in advanced age and neurodegenerative disease?

2. How can we intervene to prevent such decline?

To answer these questions, we simultaneously record from hundreds of neurons in the hippocampus of rats as they learn and perform complex memory-dependent tasks. Many neurons in the hippocampus are place cells, which fire in specific locations as a subject moves through an environment. In the movie to the right (credit: Tom Davidson), putative single neurons are each represented by a different color, and emit spikes in their “place field” as a rat (head position circled in green) traverses a u-shaped path. The reliable relationship between hippocampal neural spiking activity and spatial location allows us to use neural activity to predict the animal’s mental representation of position at any given time.

Strikingly, hippocampal neural activity doesn’t always correspond to a subject’s current position. Instead, the neural representation of position sometimes briefly represents other locations - such as where the subject is headed, reward locations, distant parts of an environment, or even other environments entirely. This “mental simulation” of previously-experienced locations is thought to be fundamental for many aspects of memory. So, what happens to place cell activity and “mental simulations” when memory is impaired?

Prior work suggests that changes in one particular form of “mental simulation,” called hippocampal replay, may be related to memory impairment. During replay, the neural ensemble corresponding to an experience is rapidly reactivated during sleep or pauses in behavior, and this repetition is thought to be critical for effectively storing the memory of that experience. This video (credit: Eric Denovellis) shows a rat’s current position (magenta) in a large, complex maze (light purple). During this 200 millisecond replay event, the neural activity represents a long traversal down one arm of the maze, even though the animal remains completely still. Replay events tend to occur during characteristic bursts of oscillatory activity in the hippocampus called sharp-wave ripples (SWRs). Studies of aging subjects and rodent models of Alzheimer’s disease have revealed a broad range of abnormalities in SWRs and replay.

Prior work suggests that changes in one particular form of “mental simulation,” called hippocampal replay, may be related to memory impairment. During replay, the neural ensemble corresponding to an experience is rapidly reactivated during sleep or pauses in behavior, and this repetition is thought to be critical for effectively storing the memory of that experience. This video (credit: Eric Denovellis) shows a rat’s current position (magenta) in a large, complex maze (light purple). During this 200 millisecond replay event, the neural activity represents a long traversal down one arm of the maze, even though the animal remains completely still. Replay events tend to occur during characteristic bursts of oscillatory activity in the hippocampus called sharp-wave ripples (SWRs). Studies of aging subjects and rodent models of Alzheimer’s disease have revealed a broad range of abnormalities in SWRs and replay.

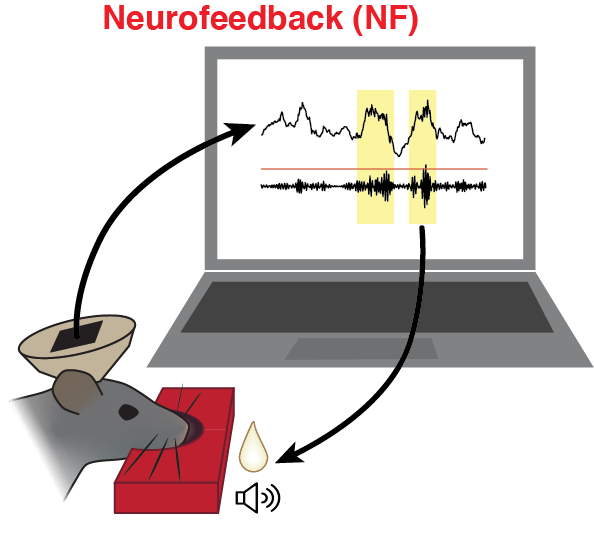

If impairments of replay, or other forms of mental simulation, are contributing to memory dysfunction in age and disease, then rescuing such impairments could be therapeutically beneficial. We have developed a method to use neurofeedback to manipulate SWRs and replay, and can now ask whether using this method to promote replay prevents or alleviates memory impairment in aged rats and in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease.

If impairments of replay, or other forms of mental simulation, are contributing to memory dysfunction in age and disease, then rescuing such impairments could be therapeutically beneficial. We have developed a method to use neurofeedback to manipulate SWRs and replay, and can now ask whether using this method to promote replay prevents or alleviates memory impairment in aged rats and in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease.

Open questions

-

How does age affect spatial representations, replay, and other mental simulations?

-

How does replay content relate to behavior in aged animals during task learning and task performance?

-

Do aging and Alzheimer’s disease affect spatial representations in different ways?

-

Do males and females show distinct changes in spatial representations with age?

-

Does aging have differential effects on awake and sleep replay?

Key approaches

• In vivo hippocampal electrophysiology • complex behavioral tasks • transgenic rat models of neurodegenerative disease • computational models • real-time neurofeedback •